Changing Rebreather Culture

In May of 2018, an experienced rebreather diver and Navy officer was doing a trimix training dive. He jumped into the water ahead of his instructor, carrying his camera, with his oxygen shut off and his rebreather in surface mode. Within a few minutes, he lost consciousness, sank and drowned.

Around the same time, in Truk Lagoon, a technical diving instructor rushed to get into the water to meet his buddy. Due to a previously noted problem with the oxygen monitoring system, his rebreather did not automatically add O2 to maintain a safe breathing gas, and no oxygen was manually added because the diver did not notice the dropping PO2 level. He lost consciousness within a few minutes, but was pulled from the water and resuscitated.

A few years ago at our local quarry, a rebreather diver was getting ready to dive, standing in waist deep water with his teenage daughter. His oxygen feed line had become disconnected. He lost consciousness and fell forward into the water, but was rescued by a nearby diver.

Accidents like these are unfortunately not as rare as they should be. No matter how clever we make our machines, ultimately they are piloted by human beings, and human beings fail. We fail when we are tired, when we are sick, when we are hungry, when we are angry, when we are distracted, and when we are in a hurry. Sometimes the failures are harmless, sometimes they are inconvenient, and sometimes they are lethal.

There is often a call for a technological fix - taking these already complex machines and add more layers of engineering to protect us from ourselves. Some of these systems do work well, but for others there are tradeoffs that can deliver unanticipated consequences, new failure modes and worst of all, complacency. Tell a diver that their machine is foolproof, and sooner or later their vigilance drops off as they take it for granted that it will always catch them when they fall. Until it doesn’t.

Analysts often refer to the “accident chain”, a series of mistakes or omissions that combine to lead to disaster. The metaphor of a chain is used to underscore how breaking one link - catching one error - can often prevent catastrophe. There is one extremely low tech method of breaking the accident chain in rebreather diving: a simple physical pre-splash checklist might have saved these three divers.

This checklist is just a few things to confirm before jumping into the water, ideally while you are already wearing your rebreather. The reason that it’s best to do it while wearing the unit is that you know that nothing has changed between checklist and splash. If you do it earlier, before donning your rig, there is plenty of opportunity for gas to get shut off, hoses to get disconnected, shutoff valves to get closed, etc…

It doesn’t take the place of the larger build checklist, which is done the night before or on a dive boat bench (calibration, O-rings, stereo checks, positive and negative checks, controller settings, etc..). That is an important but separate practice. The crucial points of the pre-splash checklist are intended to pick up problems that are most likely to be lethal without warning. And for rebreather diving, that basically means whether or not the unit is capable of maintaining a safe oxygen level.

Why don’t all rebreather divers use these? Checklists are used in the operating room and on commercial airliners with great success in improving safety records. But surgeons and pilots function as parts of larger organizationw, while divers are on their own. There is no scuba police - ultimately every diver does what they want to do. And relying on memory or mnemonics simply isn’t as good as using a physical checklist. Mnemonics often are misremembered by the people who need them most, and they depend on your mental state. No matter how tired or angry or distracted you are, that written checklist will always tell you the same steps.

My old underwater camera was in an Ikelite plastic housing, and there was a loose O-ring that was trapped between the housing and the dome port by water pressure. I always remembered to install it. For years. Never a problem. Then one day I had an argument with my wife before putting my camera together. I left it out and flooded the housing. I was able to replace my camera. But jump in with your O2 off? You may not get a second chance.

For my first year of rebreather diving, I carried my checklist on a little plastic card, which I would hold in my hand as I ran through the steps. In addition to this occupying one of my hands while I was trying to do other things, afterwards I had to either put it away or find a place to clip it on my gear where it hung like a war medal - the royal order of the newbie! And I started to get a little self conscious, diving with far more experienced divers who apparently just got ready to dive from memory. Of course, that line of thinking is normalization of deviance - I assumed that because these role models didn’t have a little card, someday I wouldn’t need one either. Maybe that’s what happened to those divers I mentioned above.

Around the same time, in Truk Lagoon, a technical diving instructor rushed to get into the water to meet his buddy. Due to a previously noted problem with the oxygen monitoring system, his rebreather did not automatically add O2 to maintain a safe breathing gas, and no oxygen was manually added because the diver did not notice the dropping PO2 level. He lost consciousness within a few minutes, but was pulled from the water and resuscitated.

A few years ago at our local quarry, a rebreather diver was getting ready to dive, standing in waist deep water with his teenage daughter. His oxygen feed line had become disconnected. He lost consciousness and fell forward into the water, but was rescued by a nearby diver.

Accidents like these are unfortunately not as rare as they should be. No matter how clever we make our machines, ultimately they are piloted by human beings, and human beings fail. We fail when we are tired, when we are sick, when we are hungry, when we are angry, when we are distracted, and when we are in a hurry. Sometimes the failures are harmless, sometimes they are inconvenient, and sometimes they are lethal.

There is often a call for a technological fix - taking these already complex machines and add more layers of engineering to protect us from ourselves. Some of these systems do work well, but for others there are tradeoffs that can deliver unanticipated consequences, new failure modes and worst of all, complacency. Tell a diver that their machine is foolproof, and sooner or later their vigilance drops off as they take it for granted that it will always catch them when they fall. Until it doesn’t.

Analysts often refer to the “accident chain”, a series of mistakes or omissions that combine to lead to disaster. The metaphor of a chain is used to underscore how breaking one link - catching one error - can often prevent catastrophe. There is one extremely low tech method of breaking the accident chain in rebreather diving: a simple physical pre-splash checklist might have saved these three divers.

This checklist is just a few things to confirm before jumping into the water, ideally while you are already wearing your rebreather. The reason that it’s best to do it while wearing the unit is that you know that nothing has changed between checklist and splash. If you do it earlier, before donning your rig, there is plenty of opportunity for gas to get shut off, hoses to get disconnected, shutoff valves to get closed, etc…

It doesn’t take the place of the larger build checklist, which is done the night before or on a dive boat bench (calibration, O-rings, stereo checks, positive and negative checks, controller settings, etc..). That is an important but separate practice. The crucial points of the pre-splash checklist are intended to pick up problems that are most likely to be lethal without warning. And for rebreather diving, that basically means whether or not the unit is capable of maintaining a safe oxygen level.

Why don’t all rebreather divers use these? Checklists are used in the operating room and on commercial airliners with great success in improving safety records. But surgeons and pilots function as parts of larger organizationw, while divers are on their own. There is no scuba police - ultimately every diver does what they want to do. And relying on memory or mnemonics simply isn’t as good as using a physical checklist. Mnemonics often are misremembered by the people who need them most, and they depend on your mental state. No matter how tired or angry or distracted you are, that written checklist will always tell you the same steps.

My old underwater camera was in an Ikelite plastic housing, and there was a loose O-ring that was trapped between the housing and the dome port by water pressure. I always remembered to install it. For years. Never a problem. Then one day I had an argument with my wife before putting my camera together. I left it out and flooded the housing. I was able to replace my camera. But jump in with your O2 off? You may not get a second chance.

For my first year of rebreather diving, I carried my checklist on a little plastic card, which I would hold in my hand as I ran through the steps. In addition to this occupying one of my hands while I was trying to do other things, afterwards I had to either put it away or find a place to clip it on my gear where it hung like a war medal - the royal order of the newbie! And I started to get a little self conscious, diving with far more experienced divers who apparently just got ready to dive from memory. Of course, that line of thinking is normalization of deviance - I assumed that because these role models didn’t have a little card, someday I wouldn’t need one either. Maybe that’s what happened to those divers I mentioned above.

The Royal Order of the Newbie

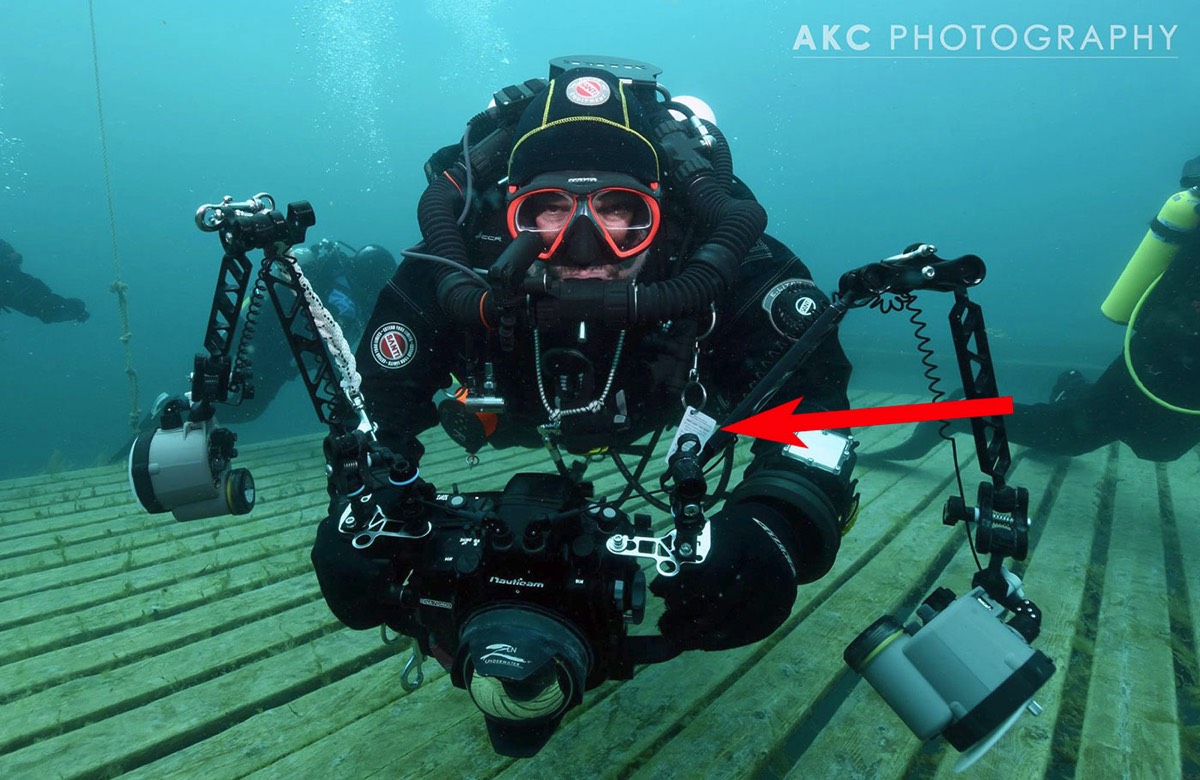

(photo by Alice K. Chong)

So I came up with the idea of printing the checklist out on a sticker and putting it on my controller, on my left wrist. Now, it’s always there, I can’t forget it, I don’t need a free hand to hold it, and I don’t need to stow it when I’m done. And if you are one of those people who worry about looking like a newbie, it’s pretty unobtrusive.

It doesn’t protect you from everything - you still need to be ever vigilant. But at least it’s a start. My hope is to change the culture of this little community of divers. And maybe someday a physical checklist won’t be seen as the mark of a newbie, but of someone who respects the sport.

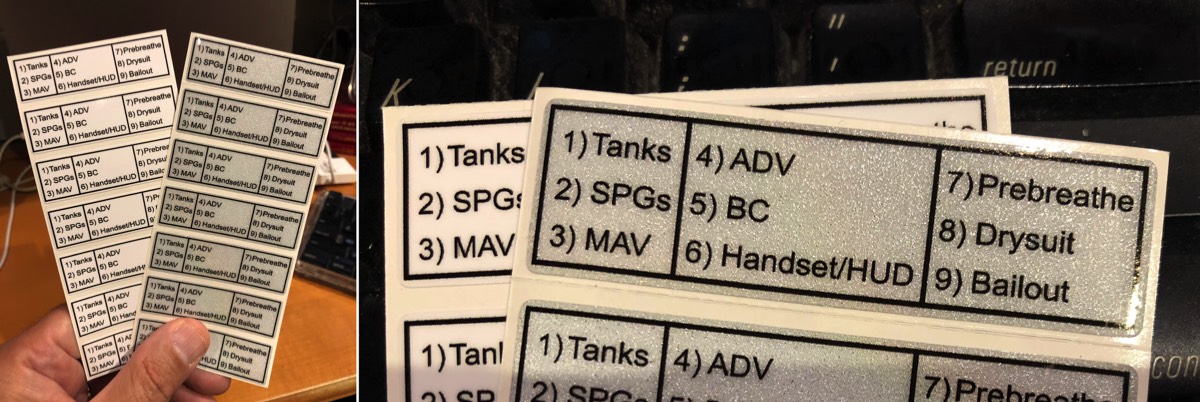

Initially, I just printed these up myself on Avery 15513 weatherproof labels. Then, I had some made up by Ray Morris, who runs DivingLabels.com. Ray is terrific, he does a great job on these. Based in the Philippines, he makes them either in plain white vinyl (9 cents each) or 3M reflective material (12 cents each). If you aren’t in a hurry, have them sent by surface mail. If you can’t wait, he will do express shipping for an additional charge. Just contact Ray through the website and ask him for Mike’s rebreather labels.

If you would rather just print your own, feel free to download the files from this page. You can use the Word document for a sheet of labels, a simple JPEG, or my Photoshop file if you want to customize it for your own checklist. I have found that no matter what type of label you use for this, it always helps to put a layer of Gorilla Glue or something similar under it.

But whatever you do… PLEASE use a physical checklist before you splash.

It doesn’t protect you from everything - you still need to be ever vigilant. But at least it’s a start. My hope is to change the culture of this little community of divers. And maybe someday a physical checklist won’t be seen as the mark of a newbie, but of someone who respects the sport.

Initially, I just printed these up myself on Avery 15513 weatherproof labels. Then, I had some made up by Ray Morris, who runs DivingLabels.com. Ray is terrific, he does a great job on these. Based in the Philippines, he makes them either in plain white vinyl (9 cents each) or 3M reflective material (12 cents each). If you aren’t in a hurry, have them sent by surface mail. If you can’t wait, he will do express shipping for an additional charge. Just contact Ray through the website and ask him for Mike’s rebreather labels.

If you would rather just print your own, feel free to download the files from this page. You can use the Word document for a sheet of labels, a simple JPEG, or my Photoshop file if you want to customize it for your own checklist. I have found that no matter what type of label you use for this, it always helps to put a layer of Gorilla Glue or something similar under it.

But whatever you do… PLEASE use a physical checklist before you splash.