Getting Started with Boat Diving in the NYC Area

INTRODUCTION

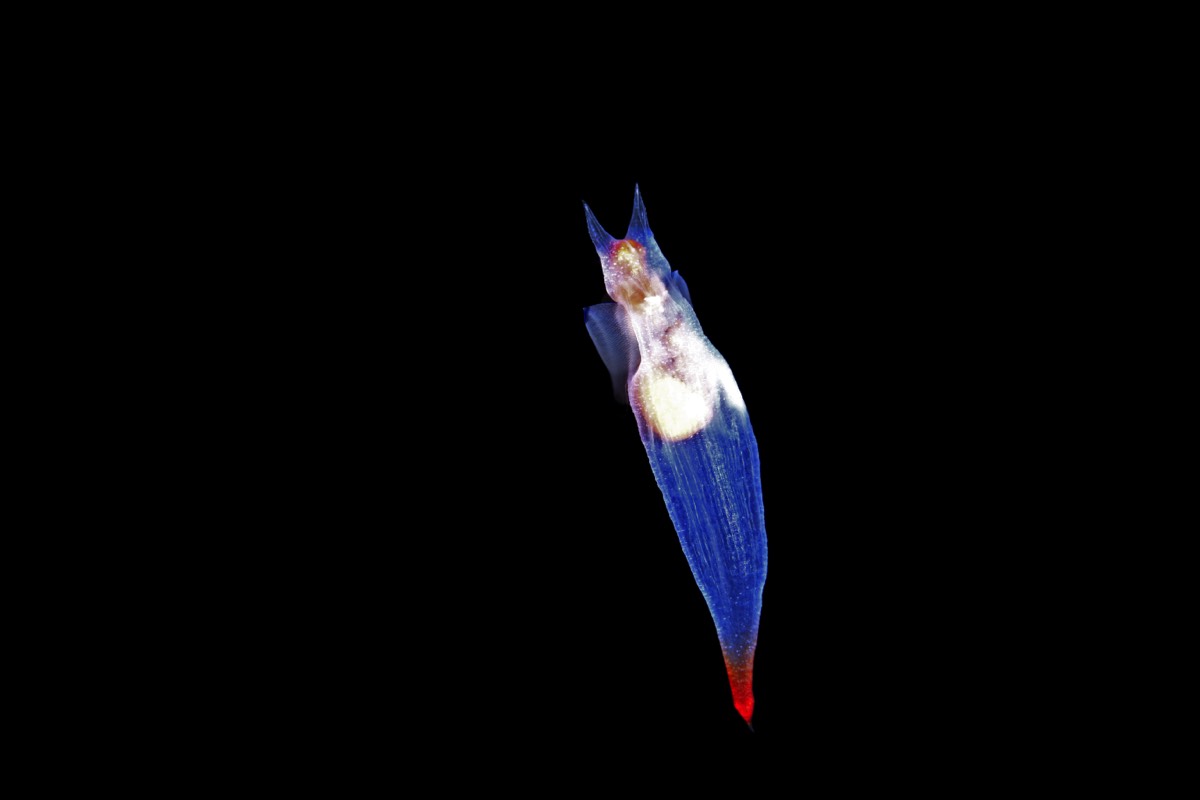

If you are reading this page, you may be thinking about getting started scuba diving in the New York City area - specifically in the New York Bight, off the New Jersey shore or the south shore of Long Island. So, congratulations! You are lucky to have such close and frequent access to an incredibly diverse and thriving marine ecosystem, as well as hundreds of historically significant shipwrecks. This article was written for people who are new to diving in our area. Some of you may be new to diving in general, but even experienced technical divers who have mainly been in tropical conditions can benefit from this review of the gear, procedures and dive culture that you will find in our region.

While many of our local dives require advanced training, there are plenty of sites that are easily within the reach of a single tank recreational diver who is willing to put in the effort to get familiar with the logistics and equipment needed to make these dives safe and comfortable. There is also terrific shore diving here, but I have focused on boat diving. The shore diving guide will have to be my next project.

LOADING

As you can see from my image galleries of local marine life, local divers and online resources for the shipwrecks and other dive sites in the area, there is plenty to see just off the shores of New Jersey and Long Island. But let's first address the two things that often keep even passionate tropical scuba divers from considering diving in their own back yard - the water temperature and the visibility.

When you first start diving in this area, especially if you are used to the Caribbean, these may seem like deal breakers. But once you start diving, you realize that you don't need 100 feet of clear water to have a fantastic dive, and if you dress appropriately for the sport, you can be comfortable year round.

While some people do dive locally in a heavy wetsuit - especially later in the summer and fall when the water warms up - the vast majority of regular local divers use a dry suit. These are not cheap, and they do require training to dive safely, but they make a huge difference in your comfort and the length of the dive season. By using different undergarments, you can dive the same dry suit in the tropics and in arctic waters. Heavy wetsuits are difficult to put on and can be very restricting. A well fitted dry suit (fit is important!) can feel as good as an old pair of pajamas. Furthermore, dry suits can have big pockets attached more easily than wetsuits, and provide redundant buoyancy in case of a BC failure. A quality wetsuit can be good for shore diving, where the shallow water is much warmer, but when diving off boats I always dive dry.

The most important thing is that if you live here and you love diving, you can dive here every weekend when the weather cooperates! You don’t have to wait for one or two weeks each year, No time off from work, no airfare, no hotels, no packing with weight limits. For someone who loves diving and who lives in our area, local diving is the way to go!

One of the best ways to get involved with the local diving scene is to join a dive club, such as the Big Apple Divers. Our club has over 300 members with a wide range of experience and training. We have everything from non-divers to new open water divers to technical instructors with thousands of dives in all types of environments. The club runs all sorts of events - lectures by some of the most famous divers in the world, a local diving schedule in the summer and fall, club trips to dive destinations out of the area, and a large number of social events where divers can just get together and chat with fellow members of the tribe!

This club promotes the kind of mentoring that helps divers who are new to diving in our area get started. While there is no PADI course in "local diving", many of our members with significant local diving experience are happy to lend a hand and pay it forward, getting the next generation of local divers excited about the sport, and showing them how to do it safely. The club runs an annual Introduction to Northeast Diving program that pairs mentors and new divers both at quarry or shore diving sites and on a charter boat for ocean dives.

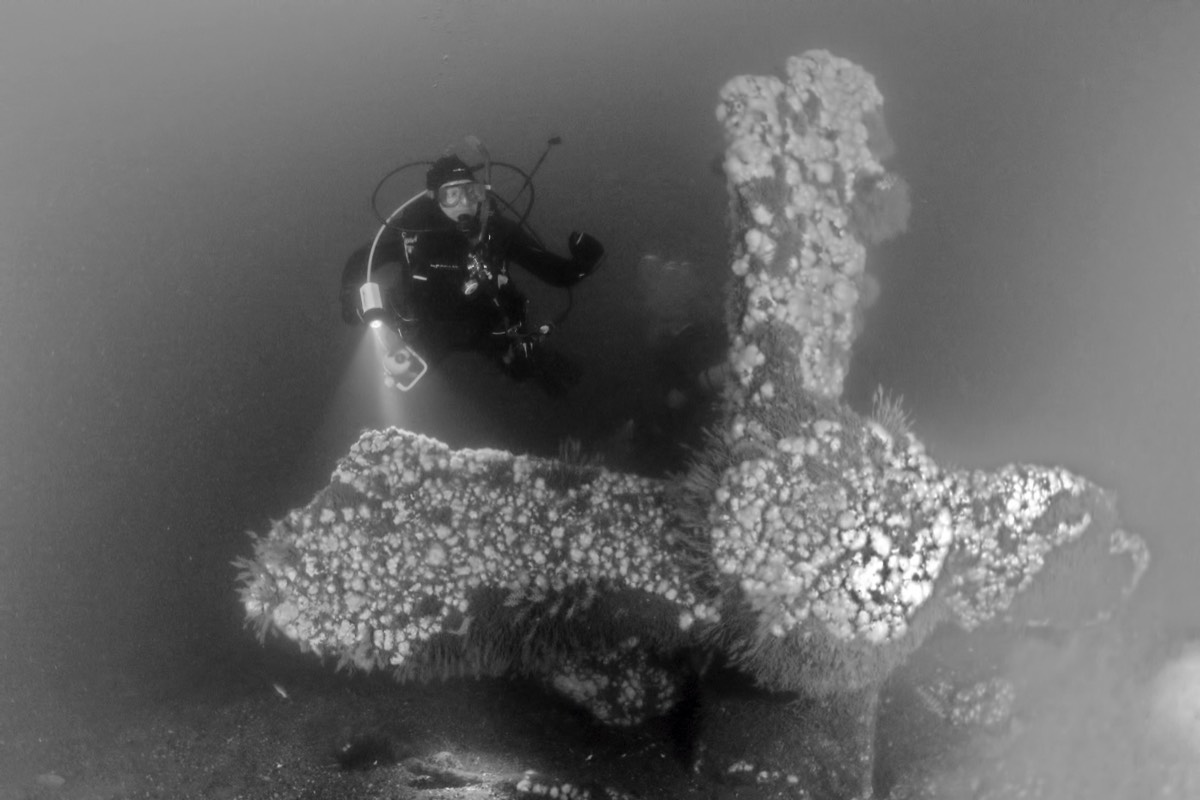

Unlike other dive destinations where most of the shipwrecks have been sunk as artificial reefs, most of our wrecks are “real”, with fascinating and tragic histories. Reading about them makes the dive much more meaningful. New York City has been a major shipping hub for 500 years, and there was a lot of German sub activity right off of ours shores during World War II. A number of our wrecks were U-boat victims, and there are submarine wrecks as well. Some of these ships are intact enough to have internal areas to explore (like the USS San Diego or the Stolt Dagali), but most of the older wrecks have been reduced to open piles of structure by the sea, storms, or wire dragging. Still, these are fascinating places where you can take photos, shoot video, collect artifacts, spearfish, and hunt for lobster, mussels or scallops.

We have a few artificial reefs, including ships, construction rubble and even subway cars, which have become the basis for a thriving ecosystem. In addition to boat diving, there is excellent shore diving in the area, where the warm, shallow waters of the inlets and bays of the coast are home to countless juvenile fish and other marine life. Popular places for this include the Back Bay and inlet of Belmar, New Jersey, the old Ponquogue Bridge on Long Island, the Manasquan River Railroad Bridge in Point Pleasant, New Jersey or even Beach 8th Street, in New York City! While there are plenty of things to learn when starting to do shore diving, this article mainly focuses on boat diving on shipwrecks and artificial reefs.

If you are used to tropical resort-type dive operations, you will find the practices, gear requirements and culture of the local diving operators to be different, and it's best to understand this ahead of time. This article, the intro program, and just hanging out with our many friendly experienced local divers are great ways to get up to speed on these topics

CHARTER BOATS

The local scuba scene is built around our charter boats. They are a precious and limited resource, and we all do our best to appreciate and support the captains and crew, but their business models are very different than those you may be used to from resort diving.

In the Caribbean, the boat owner may not be on the boat or even on the island. These operators typically cater to an ever changing group of divers with a wide range of skills. Tanks and weights are included in the price, as well as a dive guide for the group. Rental gear is usually available through the associated dive shop. The dive group is typically led on a planned course and surfaces together. Buddies are assigned by the divemaster to anyone who is alone. The boat is in the water with paying customers several days a week, weekdays and weekends, for most of the year, missing only a few days when the weather prevents diving.

On the other hand, a NYC area dive boat is generally owned by the captain, who often is out on the charters. The crew are typically experienced divers who are friends of the captain, and whose only pay is tips from the customers and the dive that they may get to do. Our season is from May to November, although some boats do run year round, weather permitting. They are out on the water primarily on weekends, and with many scheduled dives "blown out" - cancelled at the last minute due to poor sea conditions. These boats are not the cash cows that you might find in warm water dive destinations, but rather labors of love, where hopefully the season brings in enough in charter fees to pay for dockage, insurance, gas and maintenance.

Local boats generally do not provide tanks, weights, or have any options for gear rental. Some of the dives are charters by a dive shop (which will rent gear) or a club like the Big Apple Divers (which does not). Other dives are "open boats", which means that the captain is selling the spots to customers directly. There is no guide, and customers are expected to plan and execute their own dive in buddy teams that they arrange ahead of time. Some divers with solo diving certification and/or experience may choose to dive alone. The captain, crew and the chartering organization does not organize buddy teams. The crew keeps careful track of who enters the water, and of each divers planned run time, but they are not in the water with the divers. The customers tend to be regulars, although of course divers new to the NYC area are welcomed on appropriate wrecks. Sometimes, the best mentoring happens informally, as the crew and customers chat about diving on the way out and back.

EQUIPMENT

Local boats often have specific gear requirements. The most common of these are a redundant gas supply and a surface marker buoy (SMB). Check out this page for more important information about SMBs and their use. A redundant gas supply means a separate source of breathing gas that will be immediately available in case there is any problem with the primary system. Rebreather divers carry one or more "bailout" bottles for this purpose, and divers using double tanks have redundancy built into the system, with two separate gas tanks and two regulators.

For single tank divers, a redundant gas supply means a pony bottle - a small backup tank with its own regulator which is either slung off of the BC or clipped to the primary tank. Remember, this is meant to allow for a safe, slow ascent (including a safety stop) in case of a catastrophic loss of the primary gas supply. For example, this could happen with a blown low pressure hose or an unrecoverable free flow, both of which can empty a single tank in less than a minute. This gas should not be used for dive planning - a diver should never run their primary gas reserves low because they are carrying a pony bottle. It should only be used in a dire emergency, not as a crutch to accommodate poor dive planning.

Signaling devices are strongly recommended, since these dives are out in the ocean, far from shore, with potential strong currents. If you get separated from the wreck site, the boat will not be able to chase you since there may be other divers in the water. In addition to a whistle and signal mirror, some divers carry personal locator beacons, a GPS equipped radio, or surface dye markers. A slate or underwater notebook may be useful for communicating with a buddy when hand signals aren't enough. Finally, anyone diving in this area, where there are likely to be entanglement hazards (fishing line, nets or even the divers own navigation line) should carry two cutting devices. Read this important page for a discussion of appropriate choices for this purpose.

In general, "danglies" are discouraged by divers in our area. Clipping tools like SMBs and slates to your BC and allowing them to float around can create entanglement hazards and extra drag, so where possible local divers try to keep things neat, tidy and clean. Hose length and routing is chosen to avoid long extra loops of hose floating in the current. SPGs or consoles are clipped off at the far end and unclipped when needed. Pockets are very useful - most dry suit divers have two large ones on the hips. While it is possible to attach pockets to a wetsuit, these tend to come loose, so pocket shorts may be a better solution for wetsuit divers. Some BCs have pockets, but they tend to be fairly small and more difficult to access, as they ride higher than thigh pockets.

The captain is the one who determines the certification requirements for each dive. While there are a few shallow wrecks less than 80 feet deep, many of the captains require at least Advanced Open Water training for the majority of dive sites. Be sure to confirm with the boat captain and/or the chartering organization about any specific gear or certification requirements ahead of time. They may also require you to show your certification card - be sure to bring it with you.

Most divers in our area carry a few basic topside tools with them on every dive trip. You would be surprised how often something cheap and simple can be the difference between diving and not. You don't need to bring a whole dive shop with you, but a waterproof case containing spare O-rings, a multi-purpose tool, some double enders, bolt snaps, a spare mouthpiece, and a small amount of cave line may come in handy someday. And of course, a diver without zip ties is like a roadie without duct tape. Oh, yeah. Also bring duct tape.

PLANNING YOUR DIVE

Dive planning is more formal than in typical warm water resort diving, where the group turns the dive and ascends based on the reserves of the diver with the highest gas consumption rate. When diving locally, the crew will ask you your planned run time, which is the TOTAL planned time of your dive, from the time your head goes underwater to the time you surface, including all safety stops and other staged decompression (not just the bottom time). Each diver's run time is carefully recorded, so if they are late coming back, emergency protocols can be activated (like sending a crew member to look for the missing diver on the line or on the wreck). Because of this, it is ABSOLUTELY vital that you do not stay beyond your stated run time, even if you end up with extra gas or NDL time. If you do that, you will quickly find yourself on the "boat is full" list and not be welcomed back in the future!

Even if you are "just" an open water diver breathing plain air, take the time to figure out a dive plan as soon as you have booked a spot. Look up the wreck on njscuba.net, including the depth and the "relief" (how high the wreck rises above the sand). Some wrecks sit in fairly deep water but have a lot of relief, so your dive planning should take that into account. For example, the Algol is in 145 feet of water, but the main deck is at 110 feet and the top of the superstructure is at 70 feet. A local diver should be able to plan a multi level dive on this wreck, knowing how much time he or she will have at each level based on their known air consumption and breathing mix, as well as that of their buddy.

In addition to planning your dive, you will be expected to be a part of a buddy team (unless you have the experience, certification and equipment for the captain to allow you to dive solo). Ideally, you should make buddy arrangements well before the dive and discuss the dive team plan before you get to the boat. While sometimes existing buddy teams or a qualified solo diver will allow someone to join them, recognize that it is poor etiquette to go around asking for this at the last minute, and no one is obligated to dive with you. Assuming that you are new to northeast diving, chances are that your dive plan won't match up with the plan of the people that you are joining. This puts divers who are doing longer dives in an uncomfortable position. They may feel some inclination to let you join them, but then what happens when you need to surface and they want to keep diving?

Having a new diver surface alone is potentially risky, and you shouldn't let your poor planning force them to make that choice. Please ask the dive charter operator or dive club for the roster ahead of time, and make these requests long before the day of the dive. In some cases, the captain or dive organizer can suggest appropriate people to ask. This is another advantage of diving with a club - you will be more likely to find a buddy, and the club member running the dive can help you with this. Occasionally a crew member will buddy with you, but guiding new divers is not an expectation of the crew, so if someone does this you should offer some sort of extra payment. On the other hand, many experienced divers enjoy mentoring people new to the area, and may be willing to shorten our own dives to help "pay it forward"!

Local divers watch the ocean weather forecast carefully in the days leading up to a dive trip. It is important to realize that on a bright sunny day you may have big ocean swells, and on a grey, rainy morning the sea may be flat and calm. The captain makes the call as soon as they can, but usually they wait and watch the weather rather than cancelling far in advance. In some cases, they will even leave the dock, get out of the inlet, and then decide to cancel a dive right then and there. Yes, it is inconvenient (especially if you are renting a car and gear), but forecasts are often wrong, and the captain really doesn't want to cancel a dive unless it's a safety issue. The only time a dive is "blown out" more than a day or so ahead of time is when there is a major storm moving through the area. The general rule is that if the captain cancels a dive, then the fee is refunded to the divers.

Seasickness is something to be anticipated and dealt with in the northeast or in the tropics, as it can quickly ruin a dive trip. While the boats tend not to go out in very rough conditions, even a gentle rocking can cause nausea and vomiting. Take whatever medication works best for you well in advance of leaving the dock - some take it the night before. Eat a light breakfast, but eat something, an empty stomach may make things worse. Here is a more detailed review of this subject.

ON THE BOAT

Local dive boats leave much earlier than tropical resort boats, often at 6 AM. You must be at the dock at least 45 minutes before departure time to load your gear so that you can have an on-time departure. The captain will not wait for latecomers, if you are late getting to the wreck, there is a good chance that another dive boat or a fishing boat will already be there.

PLEASE do not bring large “diving” luggage on the boat. These are designed for air travel, and being wheeled through airports. They are NOT meant to get wet. On any boat it is very important to keep all of your various pieces of gear stowed cleanly and out of the way in one place. This gear will be wet, so whatever you keep it in must allow for drainage and not absorb water. A large mesh duffle bag is one solution, but most local divers use a milk crate for this. These are incredibly durable, easy to stow under a bench, and provide a convenient place to toss your gear after the dive where it won’t get lost, mixed with someone else’s equipment or broken. Stow your gear as quickly and as compactly as you can as soon as you get on the boat - you don't want to have pieces of equipment strewn all over the place. The crew will show you where to do this, as it varies from boat to boat.

Once all of the divers are on board, the captain or other crew member will give a briefing about the dive boat - restricted areas for passengers, information about the head, safety information about emergency procedures, etc... Please pay attention to this, especially if you have not been on the boat before. Do NOT whisper to others or work on gear during this time.

Try to get all of your equipment squared away and ready to dive before the engines start up, and certainly before the boat leaves the flat water of the harbor and inlet for the open ocean. It is FAR easier to assemble your BC, regulator, and weights before the boat hits the waves. Also, make sure that your rig is safely secured with bungee cords or whatever else the crew specifies - it is VERY easy for a heavy scuba unit to topple over in rough seas, potentially destroying it and causing injury.

Once your gear is assembled and secured, find a comfortable place to sit or lie down for the trip out to the dive site. In some cases, it can take an hour or two to get there. While many of us enjoy chatting and socializing during this time, don't be shy about getting some rest. Typically, you will have woken up very early and hauled a lot of heavy gear around that morning; you want to be fresh for the dive. On the way to the wreck, one of the crew members may give a dive site briefing. This is especially helpful when there is critical information about navigation issues or other aspects of the wreck that you aren't familiar with. Listen carefully, and be prepared to alter your dive plan based on new information.

Some warm water dive operators will do “drift diving”, where the divers are put into the water, the captain follows the divers by watching bubbles or surface marker buoys, and picks them up as they drift. This is often done in areas of heavy surface currents, since if both the diver and the boat are moving with the current, there is no relative movement and it’s easy to reboard the boat. This works well if you have a group entering and leaving the water together.

This is not something that is done commonly in our area of the world – rather, the dive boats “tie into” the dive site, usually a wreck. With local dives you often have people doing dives on different schedules - some doing one long dive with significant decompression, others doing two non-deco dives. The dive platform (the boat) will stay in the same place for the entire time you are on the site, immediately available for emergency procedures if necessary. Also, unlike the drift diving done in some warm water locations, our diving is typically miles off shore, in heavy shipping channels with unpredictable currents, increasing the risk of losing a diver in the open ocean.

There are a number of ways of securing the dive boat on station at the site, but this is a typical approach. Once the captain is over the wreck, a weighted line connected to a floating ball is thrown into the water. One or two crew members enter the water, go down the line and find the wreck. They then “tie in” or “set the hook” - securing the chain at the end of the line to the wreck. Once this is done, the surface is signaled (often by releasing something that floats), and the boat is tied to the end of the line. In many cases, a “Carolina Rig” is used to help divers to get to the wreck and back, and to spread out divers who are doing safety stops or decompression under the boat.

GETTING INTO THE WATER

Try to be organized and time your final equipment preparation and donning so that you and your buddy are ready to jump around the same time. You don't want to be hanging around the stern on the surface for a long time, waiting as other divers have to swim around you. Before you stand up, this is the time to do a check of your gear (regulators working, inflator hoses connected, weight belt secure, etc…). Confirm that your tank valve is ALL the way on, and that you take several breaths from your regulator while watching your SPG to make sure the needle doesn't move (a sign of a blockage of gas flow). Don't be afraid to ask the crew for help with getting all of this squared away, and with moving to the back of the boat. Many new northeast divers aren't used to the heavier gear and exposure suits. You will be wearing your fins as you walk towards the stern. It is far better to be supported as you move aft than to fall, possibly injuring yourself, others or your gear.

Most NYC area dive boats have a large "tuna door" in the transom of the stern of the boat. You will do a giant stride to enter the water, not a back roll. When you enter the water, you should have some gas in your BC to keep you buoyant initially - we almost never do "hot drops" (rapid descents) here, which are sometimes used for drift diving. Having buoyancy will give you time for a final check of your gear before descent, and the ability to adjust anything that got displaced on entry. When in the water, turn to face the crew and give them an OK sign (touch the top of your head). If there is any sort of current, grab the trail line to keep from drifting away from the boat.

LETS GO DIVING!

When your buddy team is assembled in the water, make the decision to descend together. If a Carolina rig is being used, you will go down the stern downline, forward along the granny line, and then down the anchor line to the wreck. Even if there isn't much current, PLEASE maintain contact with the line until you are on the wreck. In relatively low visibility, in mid-water with no visual references, it is VERY easy to get separated from the line and lost on the descent.

In shallow water (at around 15-20 feet), while maintaining physical contact with the descent line, stop and confirm that your team is ready to proceed. Look for bubble leaks from each others BC and regulators, check your dive computers and SPG pressures, and make sure that there is no loose or dangling equipment. If you are using a pony bottle, the regulator should be pressurized before splashing to prevent water from getting into the second stage. Some divers prefer to leave the valve open during the dive (for more rapid deployment), while others pressurize the regulator then turn the valve off (to avoid losing gas with an unnoticed free flow). Whichever approach you choose, confirm that the pony SPG shows full tank pressure on this shallow stop. Divers who choose to mount their pony bottle on the tank may need their buddy to confirm this, while the SPG on a slung pony bottle should be easily visible to the diver. Finally, take a moment to ensure that you and your buddy are communicating well, and then proceed down the line.

Once you are on the wreck, pause again to confirm that you are comfortable, and that you and your buddy are in still in good communication before leaving the tie-in point. Typically, each diver clips a strobe light with their name on it to the anchor line just above the tie in point, and retrieves it when they leave the wreck to ascend. This serves two purposes - it makes it easier to see the anchor line in poor visibility conditions, and it lets other divers know that you are still on the wreck. If there were to be a concern - if a diver was late coming back - seeing their strobe on the line means that they are almost certainly still somewhere on (or in) the wreck. If it is gone and they are not on the boat or the ascent line, that means that they may have gotten separated from the line on ascent. For these reasons, be sure to take your strobe (and ONLY your strobe) when you finish your dive.

Navigation of a wreck or other dive site can be tricky in the NYC area. Even without penetration of the wreck (which is beyond the scope of this discussion), it is very easy to get lost. You want to avoid at all costs ascending anywhere but the anchor line. Obviously, if you are lost and low on gas, you will have to do that, and there are protocols for that procedure. But this is a last ditch option, and the crew will not be happy. Doing a free ascent with no line connecting you to the site will mean that you will be drifting away with the current. Even if the captain sees you on the surface, they may not be able to follow you easily for a pickup, especially when they have other divers in the water. Please read this important page about SMBs and how to use them for a safe ascent away from the anchor line.

In many cases, local divers use a reel to place line on the wreck, so that they can easily find their way back to the anchor line. This can be a difficult skill to master, and line that is laid poorly can become an entanglement hazard - find a mentor and practice this in safe conditions. The diver laying the line goes first, followed by the other team members. When turning the dive and heading back to the anchor line, the diver with the reel goes last, with the other divers following the line before the reel operator recovers it. It is important that the reel be placed near the anchor line but not directly to it. Occasionally, the anchor line will break free from the wreck, and you want your navigation line to lead back to the tie in point.

Occasionally, visibility will be good and the wreck will be fairly intact. If divers are comfortable with the layout of the wreck, they may opt to not use a reel, especially if they are not going far from the anchor line. However, many of our wrecks look more like junkyards than ships, and you can quickly get lost if conditions are not good for natural navigation.

Many northeast divers carry powerful dive lights with tightly focused beams. In the past, most of these were canister lights with a large battery the size of a can of tennis balls on their belts, and a cable to the light head worn on the divers hand. Modern design with better batteries and more efficient LED bulbs has made some divers switch to self contained lights where the battery and light are both on the handpiece, but the old "can" lights are still widely used. While these are crucial for exploring the inside of wrecks and other unlit spaces, northeast divers have another use for these. They are our "voice" under water. With a powerful, tight beam, you can signal your buddy easily over fairly long distances.

Many casual divers doing warm water resort diving use the "plan" where they swim around with the divemaster, turn the dive when the first person reaches half a tank and follow the group back to the boat. As mentioned before, this is not something that you do in the NYC area. You need to plan your dive (ahead of time) to be sure that you are back at the anchor line with plenty of gas left for a safe ascent, including any unanticipated delays. This may change due to exertion in currents or doing a dive that is different in profile than what you had planned. Watch your gas reserves carefully, and communicate with your buddy.

The other thing that you need to watch is your nitrogen loading. Your dive computer will give you a continually updated no decompression limit (NDL). Again, if you are reading this article, I'm assuming that you are not going into deco. Remember that if you end up going deeper than your plan during part of the dive, you may run low on NDL before you are at your planned ascent time. Watch this carefully. And even if you do not have training in staged decompression, you should learn how your dive computer handles this so that you do as much of your deco obligation that your gas reserves allow. Clearly, such unplanned decompression is a major failure of planning and execution, and should be avoided.

As mentioned above, one thing that will get you in big trouble with the crew is overstaying your planned run time. It's a beautiful day, there is great visibility and no current. You are having fun with your new camera, and have been chasing a friendly mola mola around the deck of the shipwreck. You told the captain that your run time was 30 minutes, but you are at 30 minutes now and you sill have plenty of gas and NDL. So you decide to stay longer because "you are fine". Topside, no one knows that "you are fine", and they may splash a crew member to see if their missing dive team needs assistance. Trust me, don't do this.

After finishing your ascent and any stops, you will surface by the boat. Be careful not to get too close to the hull, which may be bouncing in the waves. Be aware of where it is, and use your hand to protect your head, pushing yourself away from the hull if necessary. A very full BC can make this more difficult, pushing you up into the boat. Be neutral on your final ascent, and only inflate your BC fully once you are actually on the surface.

In current, remember to maintain contact with one of the lines at all time until you are ready to climb back into the boat, even after surfacing. If there is a crowd and multiple divers are reboarding, grab the trail line, and hang back aways from the ladder. You don't want to be right underneath another diver, especially if they fall off the ladder in heavy seas. When it is your turn, follow the crew instructions for reboarding. You may want to hand up things like cameras before climbing the ladder if the seas are rough, or even clip them on to an "equipment line" which lets the crew retrieve them safely without requiring you to hand them up directly. The boat ladder is usually hinged and will be kicking in big waves, so time yourself carefully. Try to get on the lower rung when the boat is in the trough and then hang on as you and the boat ride the crest.

Unlike the tropics, most local dive boats have fins-on ladders with big steps, and the crew does not want you to remove your fins in the water. This prevents a diver from accidentally losing contact with the dive boat and drifting away with no fins for propulsion.

GOING HOME

Once everyone is back on the boat and the roll call is done and correct, a crew member “pulls the hook”, releasing the dive boat from the wreck and the lines are recovered. Once again, make sure that your rig is secured with a bungee or other means for the ride back, and that all of your gear is stowed compactly and out of the way. Remember that the ride home may be bumpy and windy - one of our club members once lost a dry suit over the side on the way back to dock!

When the crew is docking the boat, they are working hard. During this time, sit down and stay out of their way. Avoid the rails when the boat is maneuvering into the slip, and be sure not to obstruct the captain's sight lines. Once the engines are off and the ramp is in place, quickly remove all of your gear to the dock so that the crew can begin cleaning the boat. DON'T forget to tip the crew at this point.

Usually there will be a fresh water hose on the dock - this is a good time to give everything a rinse. Even if you are going to soak your gear at home, it's best to not let salt dry on the second stage of regulators or the overpressure valves of a dry suit or BC. Crystals will form if salt water dries on these items, and it is much harder to remove them once this has happened.

Finally, at the bottom of this page is a little video showing what it's like on a NYC area boat dive, as was discussed above, for those who have never done this before.

Please feel free to contact me for specific advice on how to get started. I am so grateful to the mentors who helped me in the beginning, so I always try to pay it forward. And I'm always hoping to inspire the next generation of local divers to keep our sport alive!

Michael Rothschild

This website is meant to help divers who are new to diving in the New York City area to become familiar with the specific practices, culture, gear and conditions commonly encountered here. It is NOT meant to be a substitute for formal training and certification with an appropriate instructor and agency. Every diver is responsible for their own equipment, dive planning and safety.