Seasickness and Diving

Seasickness - more generally known as motion sickness - has plagued seafaring people for thousands of years. We have detailed accounts of seasickness in Greek and Roman texts. Admiral Nelson even suffered from this malady! While he first went out to sea at a very young age, he was miserably sick on every one of his voyages. And if you start doing boat dives, you may find that you too have this (very manageable) problem.

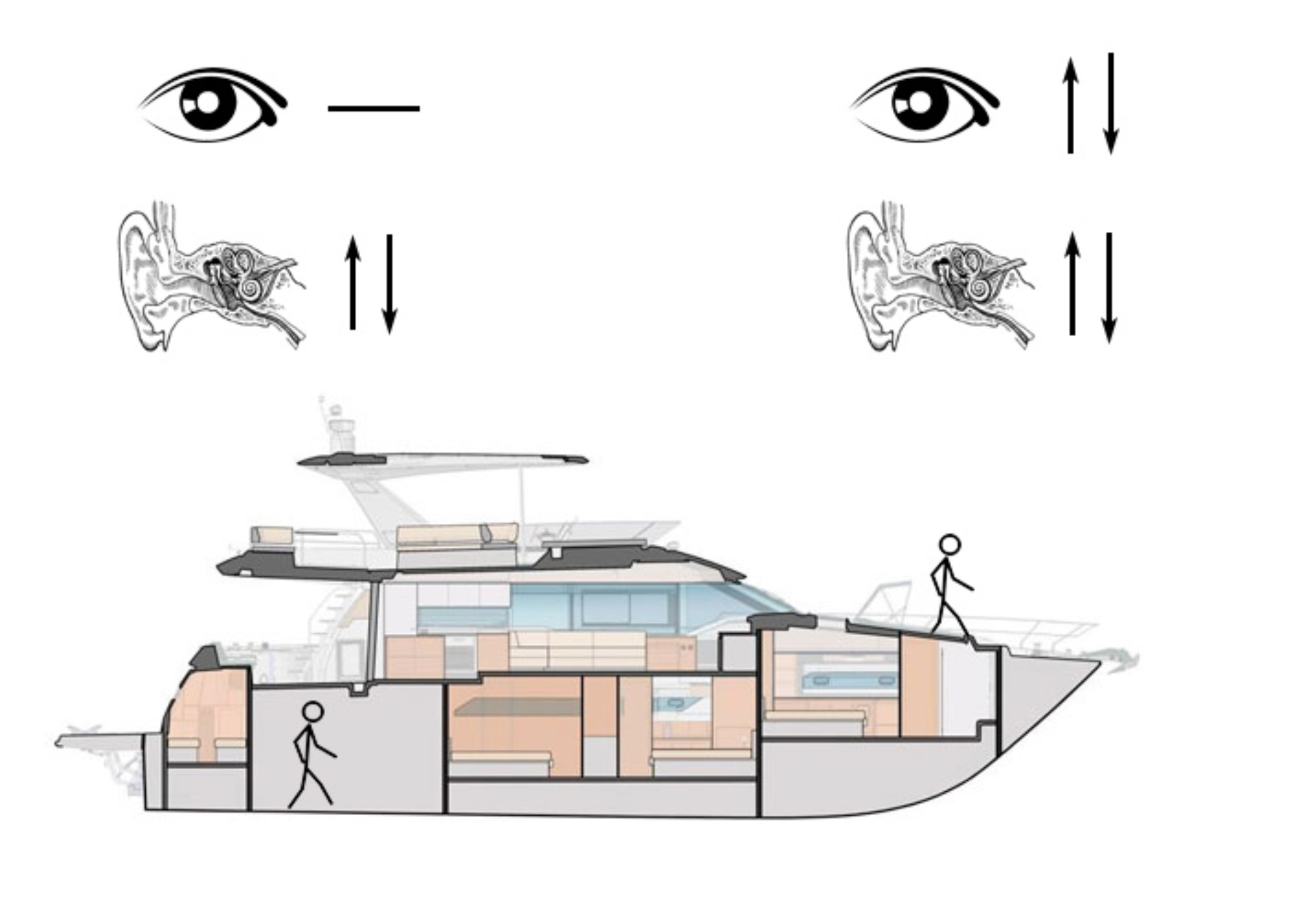

The most common explanation for seasickness is that nausea is the sensation generated by the brain to alert us of inconsistent sensory inputs. Specifically, your eyes are looking at a part of the boat which is moving up and down with you, so they tell the brain that you are standing still. But the inner ears respond to gravity and position, so they tell the brain that you are moving. The brain’s response to this disagreement is nausea.

The most common explanation for seasickness is that nausea is the sensation generated by the brain to alert us of inconsistent sensory inputs. Specifically, your eyes are looking at a part of the boat which is moving up and down with you, so they tell the brain that you are standing still. But the inner ears respond to gravity and position, so they tell the brain that you are moving. The brain’s response to this disagreement is nausea.

Seasickness is what happens when the brain gets conflicting inputs from the eyes and the inner ear. That is why staring at the horizon helps - it matches the signals from the eyes and the ears.

This is somewhat of a simple explanation, and research is ongoing in this field. The US Navy, the Air Force and even NASA have spent a lot of money trying to determine causes and potential treatment (they obviously have a vested interest). Unfortunately there isn’t a comprehensive explanation or a universal cure, but there are a number of effective methods that can help us cope with the issue.

First and foremost, do not be ashamed of being seasick. Pretty much everyone around you has been sick at one time, including the crew. The difference between the seasoned boater and the newbie is in the precautions taken to mitigate the effects of rough seas.

There is a lot of legend and lore when it comes to preventing seasickness. As everyone is affected differently, some remedies that people swear by do not work at all for others. There are, however, a few scientifically proven methods that are effective if used properly. While you may not be able to completely eliminate these symptoms, most divers eventually are able to manage them so that they can dive safely and enjoyably in typical northeast diving conditions. And of course, please consult your physician, especially if you have any medical conditions which may worsen your symptoms or interact with any of these medications.

Medication and Other Methods of Managing Seasickness

Non-prescription medication

The most common over the counter (OTC) medications used for seasickness are the first generation antihistamines. Second generations antihistamines like Zyrtec, Allegra and Claritin and not as sedating as the first generation versions, so they are more commonly used for treating allergies. However, even though the first generations drugs are sedating, they effectively treat motion sickness.

The two most common OTC antihistamines for seasickness are Meclizine (sold as Antivert, Bonine, Dramamine Less Drowsy Formula) and Dimenhydrinate (most commonly sold as Dramamine). Dimenhydrinate is actually a combination of diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and 8-chlorotheophylline, a caffeine-like stimulant. A less widely used OTC drug of this class is Cinnarizine (sold as Sturgeron).

These generally work for people that get mildly sick and if the conditions are not very rough. It is good practice to take one the night before and another one at least an hour before getting underway. If OK with your doctor these can be used in combination with prescription drugs for a combined and effective 2 prong attack.

Note that these do not work if you attempt to take them when already sick. Adding insult to injury, Dramamine is often packaged in those reinforced plastic containers that can be opened only with titanium shears. Forget opening the packages while seasick. I once chewed through the packaging for a good 20 mins during a sailboat race.

Prescription Medication

Scopolamine (also known as Hyoscine) works by a different method, acting on the autonomic nervous system to suppress motion sickness. It can be taken orally (brand names Scopace and Maldemar), but is more commonly used as a long acting patch that delivers the drug through the skin (Transderm Scop)

These are quite effective even in the most extreme cases, however they must be used with care and after consulting with a doctor. It is generally better to put on the patch the night before so that the drug is already in your bloodstream. Personally, I found that anywhere from 12-16 hours is a good rule. Others prefer a full 24 hours, and that may be advisable if the conditions are predicted to be rough. To prevent the patch from coming off I like to put some liquid band aid over it.

Note that these drugs do have side effects, the most common being slightly blurred vision, mouth dryness and mild queasiness that generally does not progress during the trip. When using the patch, it is very important not to apply it and then touch your eyes before washing your hands. There are certain medical conditions which can be seriously worsened by this drug (such as glaucoma or intestinal problem).

Promethazine (sold as Phenergan) is a prescription antihistamine, which also may be effective for severe motion sickness. However, even more than the OTC first generation antihistamines, it can be very sedating, so it is less commonly used than Scopolamine.

Other Methods

Acupressure bands (“Sea Bands”). These are stretchy bands that have a piece of plastic that presses on the inside of the wrist. They work if you believe in them (and are not prone to seasickness). Faith goes only so far. What limited research has been done on these has not shown a clear benefit.

Acustimulation bands (“ReliefBand”). This is a Battery Powered device that sends electric pulses that supposedly stimulate a nerve. These can cost about $100 and are quite annoying when in use. It never worked for me, but it adds electric shocks to the misery of being sick. Also, there is no consistent research that shows evidence of efficacy.

Ginger. Some people (mostly those that don’t really get sick) swear by it. Chewing some ginger gum or ginger root doesn’t hurt, and when you hurl at least you will have something for your breath. Again, no consistent research shows that this works for seasickness, although it is sometimes used in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Image

Dramamine Non Drowsy Naturals. This is Dramamine’s version of ginger. Also known as “non-effective Dramamine”. The advantage is that you will be brutally sick and fully awake.

Vitamin C. Some studies suggest that because vitamin C suppresses histamine release, it may be beneficial to take some prior to getting on the boat. While this can’t hurt, it’s better to find something more effective.

Seetroën glasses. This device is marketed by the car manufacturer Citroen with a claim of 95% efficacy. The idea here is to address the nausea at its underlying mechanism. By replicating the horizon in the frames of the glasses, that means that your eyes and inner ears are potentially getting the same information. Of course, the frames and the center of the visual field are seeing different things, and there is no independent evidence of their efficacy.

First and foremost, do not be ashamed of being seasick. Pretty much everyone around you has been sick at one time, including the crew. The difference between the seasoned boater and the newbie is in the precautions taken to mitigate the effects of rough seas.

There is a lot of legend and lore when it comes to preventing seasickness. As everyone is affected differently, some remedies that people swear by do not work at all for others. There are, however, a few scientifically proven methods that are effective if used properly. While you may not be able to completely eliminate these symptoms, most divers eventually are able to manage them so that they can dive safely and enjoyably in typical northeast diving conditions. And of course, please consult your physician, especially if you have any medical conditions which may worsen your symptoms or interact with any of these medications.

Medication and Other Methods of Managing Seasickness

Non-prescription medication

The most common over the counter (OTC) medications used for seasickness are the first generation antihistamines. Second generations antihistamines like Zyrtec, Allegra and Claritin and not as sedating as the first generation versions, so they are more commonly used for treating allergies. However, even though the first generations drugs are sedating, they effectively treat motion sickness.

The two most common OTC antihistamines for seasickness are Meclizine (sold as Antivert, Bonine, Dramamine Less Drowsy Formula) and Dimenhydrinate (most commonly sold as Dramamine). Dimenhydrinate is actually a combination of diphenhydramine (Benadryl) and 8-chlorotheophylline, a caffeine-like stimulant. A less widely used OTC drug of this class is Cinnarizine (sold as Sturgeron).

These generally work for people that get mildly sick and if the conditions are not very rough. It is good practice to take one the night before and another one at least an hour before getting underway. If OK with your doctor these can be used in combination with prescription drugs for a combined and effective 2 prong attack.

Note that these do not work if you attempt to take them when already sick. Adding insult to injury, Dramamine is often packaged in those reinforced plastic containers that can be opened only with titanium shears. Forget opening the packages while seasick. I once chewed through the packaging for a good 20 mins during a sailboat race.

Prescription Medication

Scopolamine (also known as Hyoscine) works by a different method, acting on the autonomic nervous system to suppress motion sickness. It can be taken orally (brand names Scopace and Maldemar), but is more commonly used as a long acting patch that delivers the drug through the skin (Transderm Scop)

These are quite effective even in the most extreme cases, however they must be used with care and after consulting with a doctor. It is generally better to put on the patch the night before so that the drug is already in your bloodstream. Personally, I found that anywhere from 12-16 hours is a good rule. Others prefer a full 24 hours, and that may be advisable if the conditions are predicted to be rough. To prevent the patch from coming off I like to put some liquid band aid over it.

Note that these drugs do have side effects, the most common being slightly blurred vision, mouth dryness and mild queasiness that generally does not progress during the trip. When using the patch, it is very important not to apply it and then touch your eyes before washing your hands. There are certain medical conditions which can be seriously worsened by this drug (such as glaucoma or intestinal problem).

Promethazine (sold as Phenergan) is a prescription antihistamine, which also may be effective for severe motion sickness. However, even more than the OTC first generation antihistamines, it can be very sedating, so it is less commonly used than Scopolamine.

Other Methods

Acupressure bands (“Sea Bands”). These are stretchy bands that have a piece of plastic that presses on the inside of the wrist. They work if you believe in them (and are not prone to seasickness). Faith goes only so far. What limited research has been done on these has not shown a clear benefit.

Acustimulation bands (“ReliefBand”). This is a Battery Powered device that sends electric pulses that supposedly stimulate a nerve. These can cost about $100 and are quite annoying when in use. It never worked for me, but it adds electric shocks to the misery of being sick. Also, there is no consistent research that shows evidence of efficacy.

Ginger. Some people (mostly those that don’t really get sick) swear by it. Chewing some ginger gum or ginger root doesn’t hurt, and when you hurl at least you will have something for your breath. Again, no consistent research shows that this works for seasickness, although it is sometimes used in patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Image

Dramamine Non Drowsy Naturals. This is Dramamine’s version of ginger. Also known as “non-effective Dramamine”. The advantage is that you will be brutally sick and fully awake.

Vitamin C. Some studies suggest that because vitamin C suppresses histamine release, it may be beneficial to take some prior to getting on the boat. While this can’t hurt, it’s better to find something more effective.

Seetroën glasses. This device is marketed by the car manufacturer Citroen with a claim of 95% efficacy. The idea here is to address the nausea at its underlying mechanism. By replicating the horizon in the frames of the glasses, that means that your eyes and inner ears are potentially getting the same information. Of course, the frames and the center of the visual field are seeing different things, and there is no independent evidence of their efficacy.

What to do While DIving

The day before

Preparation starts early.

Avoid alcohol. If you must drink limit yourself to something light and drink lots of water with it. Hydration is key. If you drink a pint of beer drink two pints of water. Avoid hard liquor.

Get a good night’s sleep. Try to sleep at least 7-8 hours. If you live far from the boat consider getting a hotel room nearby. It is typical for divers to share a room and avoid getting up in the middle of the night.

Take your medications. Most medications take some time to be effective. Usually taking a dose the day before assures that the drug is in your system and more effective.

Watch what you eat. Avoid heavy, greasy food. Do not overeat.

The morning of the dive

Take your medication as soon as you wake up. Keep a glass of water and your medications on the nightstand.

Eat something. Even if you get seasick on a regular basis make sure you do not have a completely empty stomach. Avoid greasy food but do munch on some saltines or wheat thins.

Hydrate. Drink plenty of fluids, especially something with electrolytes like coconut water. Avoid sugary beverages.

Get to the boat early. Be at the boat, with all your stuff organized an hour or more before departure. This will allow you to get the best spots and set up your gear before leaving the dock.

Prep your gear. Set up all your equipment so that you do not have to tinker with anything once the boat is underway. That means put your BC on your tank, regulators connected and tested. All your accessories should be laid out, preferably in a milk crate under your seat. Everything within reach. Some of us chronically affected by seasickness can find and put on all our gear with our eyes closed by touch alone.

Choose your seat. Sit as close as possible to midship. Avoid the stern (the back) because it is more subject to motion and it’s where you are more likely to be hit by engine fumes. Some boats have an elevated observation deck. Don’t even think about going there, it swings back and forth much more than the deck does.

Avoid the head. Use the bathroom before the boat leaves the dock – the one in the marina, not the head in the boat. Once you are at sea you may need to use the head, but for now use land based facilities.

Gear up. Getting into your suit is one of the critical tasks that is most likely to get you sick. Usually people suit up just before getting in the water. The problem is that just before the crew announces that “the pool is open” they will have spent some good time circling the wreck, bobbing about and taking waves from all different directions. Add to that the diesel fumes that now surround you and you have a perfect storm for seasickness – for those of us prone to motion sickness, this is hell. Actually, hell would appear as a welcome salvation. Always ask how long the boat ride is and depending on the answer consider gearing up partially or fully. For drysuit divers the hardest part is getting into the bottom part of the suit. Consider doing that while still at the dock, that way you only have to pull up the suit once you are at the dive site.

If you have wetsuits or drysuits with pockets (why wouldn’t you?) now is the time to clip items to your pocket bungees and stow them. The more small detail work you can get out of the way the better.

Generally speaking, if you have a very short ride, consider getting fully geared up and ready to splash prior to the boat leaving the dock. While this is easy in some locations, in the NE it may be more challenging given the long boat rides (3+ hours in some cases).

Underway

Relax. Stay seated comfortably (look at the horizon) or lie down (eyes closed). Avoid reading or tinkering with gear. Talking with others sometimes helps, most of the times is does not. If you decide to sit up, look at the horizon even if you are talking to people. They know. Fresh air also helps but beware of the exhaust fumes.

Devices & books. A big no. Do not look at your phone and do not read a book. For real. It can wait.

If you get seasick and feel that you are going to barf, head to the “barf points” designated by the crew – usually on the midship rail or gunwale. Remember to choose the downwind side – do not barf against the wind (wind always wins). Do NOT go into the head, this is the worst place to be seasick. Not only is it unventilated and hot, but it often smells terrible, making your seasickness worse. If you barf and miss the head, you will make a big mess, which will make you very unpopular with the crew. If you barf into the head, you will clog it, which will make you very unpopular with everybody.

Once the boat gets in proximity of the dive site the crew will usually give a 15 min warning. This is when most divers wake from their slumber and start getting ready. Depending how you are feeling, this is a good time to finish preparation. A boat underway tends to be more stable (depending on ocean conditions), so slowly going through the final preparation steps may be more comfortable.

Circling the dive site

Eventually you will hear the engines throttling down. That signals that you are now approaching the dive site and the captain is getting ready to send a diver down to tie off. This also signals one of the worst times for the seasickness prone among us. The boat will start circling the drop zone so it will start bouncing around quite a bit. More often than not, diesel fumes will surround you. Avoid doing anything during the mooring procedure. Try to look at a fixed point on the horizon and hold it together (if possible). Having a bucket handy is reassuring . Make sure you have noted the “barf points” on the boat in advance, although be aware of the crew’s activity during the mooring process, so as not to get in their way.

After a few minutes (that will seem like hours) you will hear the engines shut off. Wait a couple more minutes for the boat to settle down into the current.

Now you will be able to get in your gear and make those final preparations. Ask the crew for help when you need it (don’t forget to tip!!!). Avoid staying too long on the boat, get in the water as soon as you are ready and make sure you coordinate with your buddy to be ready together.

After the Dive

Once you are back on the boat and seated at your place take a few minutes to relax. Take your mask and hood off and sit for a few minutes with your eyes closed to catch your breath.

The Ride Home

While you shouldn’t leave a mess on the deck, if you are prone to seasickness then immediately after diving might not be the best time to get all of your gear packed up for unloading the boat. Keep things reasonably shipshape, but you can certainly wait to disassemble your rig for now, at least until you are in the calm waters of the inlet. This is another good time to hydrate and sleep if you can.